What ever are we doing but trying to uncover the structures that govern everyday life, the structures that are embedded so deeply in tradition that we do not even realize their strong framework in our lives?

I’m not concerned with what things are, I’m concerned with how they are.

All media intends uncover these hidden ideologies by trying to capture the essence of something in a painting, song, film, sculpture, whatever. Whether it conveys a moral, tells a narrative or expresses a world view, media describes a specific society in place and time. In producing

media, it appears as though we are trying to understand our world by capturing an objective representation of it, by taking our subjective perception and turning it into something we can physically watch or hold onto or show to someone else, which would somehow make our lonely passing thoughts seem more real. In the case of the Surrealists, representation could be used as a tool to reveal the unconscious structures at work in our own minds (similar to methods of psychoanalysis in Freudian theory.)

media, it appears as though we are trying to understand our world by capturing an objective representation of it, by taking our subjective perception and turning it into something we can physically watch or hold onto or show to someone else, which would somehow make our lonely passing thoughts seem more real. In the case of the Surrealists, representation could be used as a tool to reveal the unconscious structures at work in our own minds (similar to methods of psychoanalysis in Freudian theory.)The Surrealists asked questions about the nature of the frameworks of reality by analyzing dreams and attempting to represent their spontaneous (often libidinal) desires. In doing so, the Surrealists’ art made everyday life appear strange in ways that made us viewers wonder just how it is strange, how it is different than everyday life. In painting a clock, the Surrealists ask, what is it that makes a clock a clock, and why can it not be square, and why can’t it go counterclockwise, and why do I need to paint so-called “hands” when there are other ways to point to time? How did this tradition of making clocks, and looking at clocks, come to being?

(Still Life with Old Shoe, Juan Miro, 1937)

It can be said that in our attempts to make media, we are forced to analyze the way our ideologies trap us into a certain way of looking at the world. We see how we can never truly penetrate what something is because we are only looking at it from a certain vantage point, a vantage point that does not have access to the collective mind. Thus, art becomes a dialogue between competing vantage points, a constant conversation between artists of the past and artists of the present about how something is:“An artwork is not a unified whole, but rather an open-ended site of contestation wherein various cultural practices from different classes and ethnic groups are temporarily combined…every visual language is not merely a tool for political struggle, but by its very nature a location of ongoing political conflict.”

Art and media indeed serve as a locus for conversation between ideologies of Self and Other. Art in this sense becomes a powerful tool in shaping our construction of reality, since it acts almost as a record book or journal of multifarious traditions, and can open us up to the ideology of the Other which we may not be able to see elsewhere. Further, seeing the ideology of the Other will make us understand the distinctions between Us and Them which ultimately uncover the structural differences at work.

(Olympia, Edouard Manet, 1863)

Consequently, art becomes a political meeting place, a place where the most influential infrastructure of all— the government— is actively questioned and re-evaluated. Art in fact becomes dangerous in its ability to reveal the trappings of the structure of the government and leads artists to become subversive members of society and their art to become avant-garde, to try to break free. In fact, during the Red Scare and McCarthyism, strong censorship was placed on modern US artists because their extremely abstract work resembled the work of European art movements (Dadaism, Futurism, Expressionism, Social Realism) and therefore must have promoted Communist ideals:”In an eloquent public lecture of 1944, Robert Motherwell correlated the role of avant-garde art with all of democratic socialism and expressed deep alienation from the dominant economic system as well as its concomitant ideological values.”

Art, here, is seen by the government as so loaded with ideological potency that it needed to be hushed in order for the American public to believe in Capitalism without doubt. Art that was made by socialists or resembled socialist works being made in Europe at the time was seen as degenerate and was pulled from shows. The American government’s intense concern with the media’s reflection on their culture shows both the strong ethnocentricity of America and the power of art, in many dimensions, to show how a culture operates.

(Jackson Pollock 1948)

Since the conditions of our reality is often enforced by structures much bigger and more complex than one can understand, like censorship by the government or even one’s own subconscious, I suggest that we cannot let the "givens” in life go unquestioned. We cannot let the values deeply, deeply embedded in us trap us into looking at the world from a single vantage point. It is for this reason that producing and consuming art and media should be regarded with utmost importance in daily life. Especially in times of such fast globalization, art and media can help us understand the global community (and ourselves) in more depth, and therefore help us to adapt more gracefully to the series of shocks that modern life entails. I insist that when we explore the ideologies that govern the way we view the world, we are readier for the curveballs that it might throw at us. As Barnett Newman explains:“It’s the establishment that makes people predatory…Only those are free who are free from the values of the Establishment.”

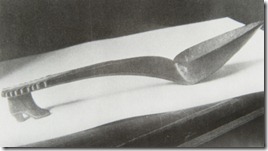

(quotes from David Craven’s “Abstract Expressionism and Third World Art: A Post-Colonial Approach to American Art. Also pictured is Andre Breton’s “Slipper Spoon,” an idea that came from a dream.)

No comments:

Post a Comment